The Supreme Court restated the conditions for one to qualify to be called a bonafide purchaser for value without notice and the sufficiency of procedural fairnesss before the Commissioner Land Registration in Kushaba Ronald v Commissioner land Registration and Jane Bitali Bisaso Civil Appeal No. 004 of 2023

Brief Facts

The suit land subject of the appeal is part of the estate of the late Lulandabala Saulo comprised in Block 83 Plot 5 land at Kagenyi. The late Lulandabala was originally registered on Final Certificate No. 10229 (FC) measuring approximately 636.8 acres.

The FC was updated to unascertained portion plots locally referred to as “blue pages” from which the late Kezironi Zirimala was registered on Block 83 of the same plot measuring approximately 40 acres.

The Administrator General was granted Letters of Administration to the estate of the late Lulandabala by the High Court in 2001. The Administrator General was registered on Plot 5 as the administrator of the estate of the late Lulandabala on the basis of the above letters of Administration.

The Administrator General being administrator of the estate caused the subdivision of Plot 5 to Pot 6 and 7 and transferred the 40 acres to Kezironi Zirimala who was a beneficiary to the estate of the late Lulandabala Saul and the 40 acres were now comprised in Plot 6 of Block 83. Kezironi Zirimala sold the 40 acres to Jayne Kalumba who sold and transferred the said Plot 6 to the 2nd Respondent who is now the current registered proprietor. Plot 7 is currently in the names of the Administrator General as administrator of the estate of the late Lulandabala Saulo.

However, without letters of administration, Christopher Bbosa Serunkuma, one of the great grandsons of the late Saulo Lulandabala, purportedly sold 91 acres forming part of the estate of the late Lulandabala to Nkaada Daniel. When Nkaada Daniel went to survey the land, he engulfed portions which were not sold to him and created a title for the original Block Plot 5 measuring 91.708 hectares instead of the 91 acres. Nkaada Daniel got registered in March 2003 and purportedly transferred this land to the Appellant who got registered on title on 18th January 2008.

The Commissioner Land Registration upon discovery of the erroneous certificate of title, notified the Appellant of his intended cancellation of title and having heard from the Appellant’s lawyers, proceeded to cancel the title.

Thereafter, the Appellant filed a suit against the Respondents to which the 2nd Respondent counter-claimed. The suit was determined in favor of the 2nd Respondent and the Appellant appealed to the Court of Appeal which equally dismissed his appeal and he preferred a second appeal to this Honorable Court.

Determination by the Supreme Court

The Court in determining whether the Appellant was a bonafide purchaser for value without notice held that one of the requirements a person must satisfy to qualify is the possession of a valid certificate of title which means a certificate that is known in the register.

The Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts’ findings that the appellant unlawfully obtained his certificate of title. Court emphasized that the system established under the RTA envisages that only the registered proprietor can lawfully transfer an interest in land. On the facts, the Court found that the appellant become registered pursuant to a transfer from a one Nkaada at a time when the owner of the suit land was the Administrator General in his capacity as the administrator of the estate of the late Lulandabala. The appellant’s predecessor in title Nkaada purportedly acquired his interest by purchase from one Christopher Bbosa Sserunkuma an alleged beneficiary to the estate of the late Lulandabala. However, when Bbosa purported to sell to Nkaada, he was not the administrator of the estate of the late Lulandabala and thus had no power to sell. In addition, the Supreme Court further found that the Appellant’s certificate of title was not backed by the register, that is, it had no root in the register due to the fact the area schedule form tendered in evidence did not prove trace the Appellant’s title to the original proprietor. Supreme Court emphasized that it is worth noting that the area schedule form records the history of transactions affecting a piece of land.

The Supreme Court having analysed principles for bonafide purchasers for value without notice concluded that; for the law to protect a bonafide purchaser from ejectment on account of the fraud of his/her transferor, he or she must be in possession of a valid certificate of title, which is known in or supported by the register.

Based on the evidence, it is more probable that the appellant’s certificate is unknown in the register since it is not supported by crucial documents such as the area schedule form. The appellant’s certificate of title was most likely a forgery which was not obtained through a legitimate process especially since the actual registered proprietor of the suit land has always been the Administrator General who never transferred any interest to Nkaada, the appellant’s predecessor. Following the vesting of the property in the Administrator General, the root of title of Daniel Nkaada to the suit property cannot be rcognised or traced to a legitimate source from the materials on record. This renders it a nullity. Accordingly, as each of the lower Courts found, the appellant did not possess a valid certificate of title for the suit land, and therefore, he did not satisfy the element of possession of a valid certificate of title as a precondition for being a bonafide purchaser for value without notice.

The Supreme Court restated the position that the nature of procedural fairness before the 1st Respondent need not involve the traditional trial process expected from court proceedings. Court did not agree that the Commissioner land Registration should have conducted an oral hearing akin to hearings conducted in Courts so as to satisfy the requirement of a fair hearing. A fair hearing was said to be sufficient when the 1st Respondent communicated the allegations made against the Appellant and gave him an opportunity to respond thereto and that this was achieved by the Appellant’s response thereto. That the Commissioner Land Registration arrived at his decision based on the papers explaining the parties’ respective interests which is sufficient to accord a party a fair hearing.

The Court stated that anyone besides the actual aggrieved party can make a complaint to the Commissioner Land Registration availing facts to aid in her investigation pertaining the rectification of a Register. What is material is that the decision to rectify the register must be made by the Commissioner in a manner that is fair and just. There was sufficient reason to doubt the Appellant’s title and have it cancelled and thus it was immaterial that the Complaint was lodged by third parties and not the 2nd Respondent. The Court rejected the Appellant’s argument that there was no fair hearing simply because the Complaint for cancellation of a title was brought by third parties who included State House Legal Department, RDC Gomba and PPS to the President.

Regarding the power of the Commissioner Land Registration to cancel a certificate of title, the Court held that upon proper construction of the relevant laws, the correct position is that the Commissioner Land Registration has no powers to cancel a certificate of title under the RTA framework without resort to Court. However, the Commissioner Land Registration has powers to cancel a certificate of title for reasons stated in Section 91 of the land Act without recourse to Court.

Court found that a party is estopped from bringing up a ground in the appeal that was not originally pleaded in the main suit. The issue regarding the legality of the letters of administration was never raised at the Trial Court. That the Appellant should have sued the Administrator General but he never did so. The Appellant was not even a beneficiary to the estate of Kezironi Zirimala and thus had no locus to argue on behalf of the estate.

The Supreme Court also revised the order pertaining to costs. The High Court had ordered each party to bear their costs. However, the Court of Appeal in dismissing the appellant’s appeal awarded the costs in the High Court and Court of Appeal to the 2nd Respondent. The Supreme Court found that the order by the High Court on costs had not been challenged in the Court of Appeal and thus it was erroneous for the Court of Appeal to have reversed the same in absence of an appeal against it.

The Supreme Court also held that the Commissioner Land Registration is a government official with an office funded by tax payers’ money which facilitates the counsel that appears on his behalf and thus costs should not be awarded to the Commissioner Land Registration to be paid by the Appellant, a private individual.

Consequently, the Supreme Court found that the appeal had failed on all grounds, thus dismissed it with costs to the 2nd Respondent and upheld the findings of the High Court.

The above ruling has thus set a precedent on the following principles of law.

- In determining whether a person is a bonafide purchaser, the Court must first establish the validity of the Certificate of Title which is rooted in the register.

- Once a person cannot establish the root of his title to a legitimate source, the question of being bonafide purchaser for value does not even arise.

- The Commissioner Land Registration can rely on written response to cancel a certificate of title without conducting an oral hearing.

- The Commissioner Land Registration can cancel a certificate of title based on information obtained from third parties.

- Courts should not award costs to government offices since their counsel are usually paid by the taxpayers.

A Court of appeal cannot reverse a trial court’s holding that each party should bear its own costs unless there is an appeal against such an order.

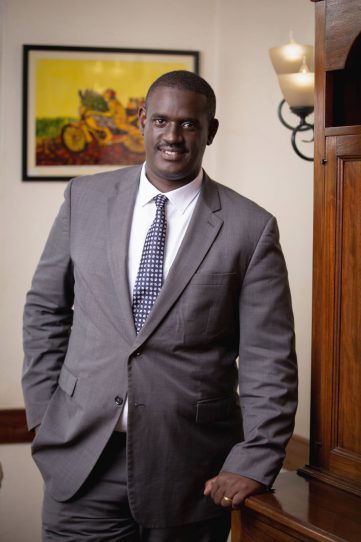

We are happy to have represented Jane Bitali Bisaso and we thank the KAA team comprised by Elison Karuhanga, Rayner Mugyezi and Ferdinand Tumuhaise for having represented our client and won in all the three Courts.